Written by Joanne Sims, Virginia Commonwealth University

Good Bye Spring Break, hello social distancing

It was a rare occasion that the news was on in the middle of my spring break. The first COVID-19 cases had just spread to Virginia. Suddenly the post-midterm peace was pushed aside for a pandemic.

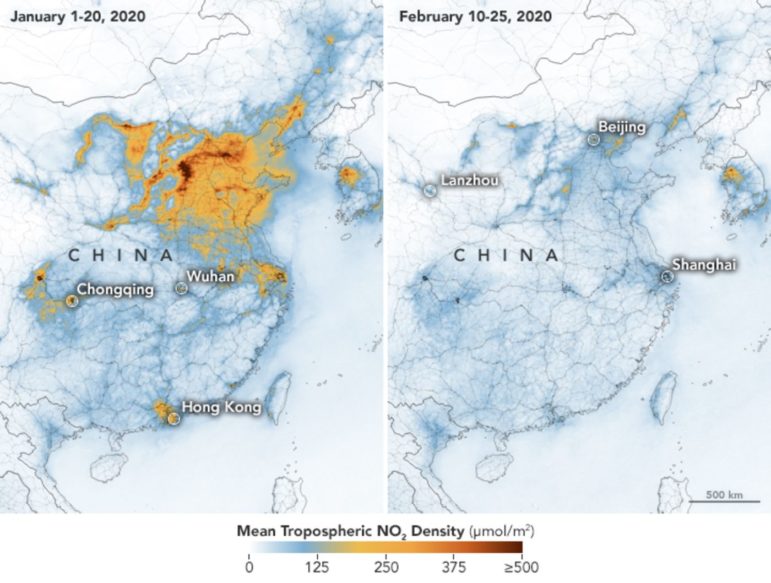

About a week into “stay at home” my socials became littered with “the earth is resetting itself” type posts about how the oceans and sky were cleaner now that we all stayed inside and it made me a little fearful. Climate change, an issue you can’t see, was still happening whether I went outside or not. Suddenly all my classes were discussing COVID-19 impacts on sustainability practices and public health.

Jack of all trades! How I became a student, teacher, and caretaker all at once.

I had already planned to go back to my mom’s house for part of the break so I just headed there with way fewer clothes than would eventually be required. My spring break got extended to two weeks when the stay at place order and school cancellations were announced. Thankful for my mother free child care was delivered right at her doorsteps (Me!).

I have two younger siblings, one in pre-school and one in high school. My new role became part time-grad student and substitute teacher. My day consisted of waking up, doing pre-K worksheets, prepping breakfast and lunches, and organizing a schedule of daily classwork for my high school sibling.

This was my first semester in graduate school, studying sustainable planning. Switching to an online format was… WEIRD. I’ve only done 1 class online before and hated every second of it. Writing memos on environmental impact assessments with Peppa Pig blasting in the background is far from ideal.

Thankfully most of my professors were pretty chill and the amount of work required this semester was reduced and altered to better fit an online format. The worst part of virtual learning is honestly discussions on zoom. I used my phone for the first couple weeks because my laptop broke just in time for online classes. Trying to find a time to interject when you can only see a quarter of the class and it feels like your professor is looking right at you is an introvert’s nightmare.

We had a discussion in my environmental policy and planning class about whether this prolonged isolation will cause a surge in suburban living. The resources strain of urban spawn is less than ideal environmentally, but the idea of having space at a time when parks and other public green spaces are closed is appealing.

Being at my mother’s house where we have a yard and the ability to not run into anyone was nice at first but something about being able to see and hear people from your 2nd-floor window has a kind of peace to it as well. It is my hope that we’ll see a rise in tiny green spaces, more apartments with courtyards and balconies at least.

I’ve been really thankful that my family has been safe and pretty fortunate so far. My mom’s job actually decreased her hours in order to limit the number of people in the building. They even gave masks to all the employees and their family members.

I definitely think being in the house with my family, who I normally see a couple of times a month, has been very stressful. Homework and babysitting don’t always agree with each other. I took a short oasis to my apartment to work on the finals. This increase in family time has made me value my peaceful one bedroom.

One of my biggest concerns during the pandemic has been my grandmother. She doesn’t drive and relies mainly on carpools and public transportation and the majority of her time was spent at church in large group settings.

I’ve been in charge of ordering all her groceries and working as tech support so she can video call family. Grocery delivery is super easy but she isn’t very adept with technology so a lot of my free time has been occupied with opening facebook’s lives of her pastor.

My next goal is to get her to figure out how to open Netflix or at least send her some DVDs so she’ll stop impulse buying from catalogs out of boredom. She called asking if I could send her a VHS player so I got my work cut out for me.

Looking into the future

Prior to the pandemic, I was feeling wishy-washy about my future. I was thinking about leaving graduate school but the state of the economy is making a Masters degree look more appealing. I’ve only been on the job/internship hunt for a couple of months and since COVID I’ve noticed a significant drop in job opportunities. I’m still hopeful but I’m definitely expanding my net to things that weren’t necessarily interesting to me.

I have a bachelor’s in Environmental Studies and I’m not sure how a lot of the non-profit work I’m interested in will be fairing during a recession. An economic downturn won’t help already disinterested people care about the topic of climate change but it should.

The speed of how quickly things turned from bad to worse with the pandemic can happen with our environment. It also gave me hope, seeing how quickly we’ve adapted to things like social distancing.

Hopefully, this shows people that fast-pace advancements for the health of our country are feasible and that we are resilient when it comes to change.