Less than 100 hours remain until the People’s Climate March — the biggest climate march in history.

Here’s what you need to know to join CCAN as we make history together in New York City:

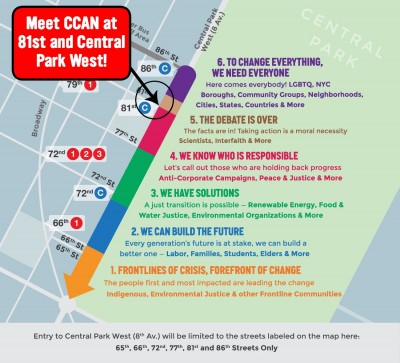

1. CCAN Meet-Up: On Sunday, September 21st, marchers will assemble on Central Park West between 65th and 86th Streets. The march will be made up of contingents coming together around shared themes. CCAN will be marching with the Anti-Fracking group, within the “We Know Who Is Responsible” bloc.

Meet up with CCANers on the corner of 81st Street and Central Park West. We’ll be with the giant Stop Cove Point Pipeline! Sign up here to march with CCAN, and we’ll send you any last-minute updates on the meet-up location. For a map of the line-up, closest subway stops and more, check out the march logistics page here.

2. Flow of the Day: The march begins at 11:30 AM — but we suggest showing up early, especially if you want to be in one of the specific contingents. CCAN staff will be at the corner of 81st Street and Central Park West beginning at 8:00AM, so come early to hang out and check out our new CCAN t-shirts for sale. (Again, sign up here for updates). The march will end on 11th Avenue, where there will be beautiful art, music, and a closing ceremony for all who can stick around.

3. Transportation: There are over 400 buses and trains heading to the march. Click here to find one from your region. Buses will be dropping off at 86th Street and Central Park West. Please check in with your bus captain about departure times and locations.

4. Housing is still available: New Yorkers, despite their reputation, are very nice, and are opening their homes and churches to folks like you coming to town for the march. Click here to find housing for the People’s Climate March.

5. All weekend long amazing events are happening: The Youth Convergence will be a space for students to come together and share campaign knowledge. Divestment groups are meeting up to compare strategies. On Monday, thousands will “flood” Wall Street for a major sit-in. There’s a lot you won’t want to miss, so check out all the events here.

This isn’t a moment to miss: With the major United Nations climate summit following just two days after our march, every major news outlet across the world will be watching. And if we make this march bigger than any climate mobilization ever before, we, the people demanding bold action will be in every single one of those stories.

Join CCAN at the People’s Climate March. It’s going to be amazing.

Calling all Virginia students: Are YOU marching?

I’m Drew. I’m the new Virginia Campus Organizer at CCAN, and I can’t wait to dive in and support all of the amazing youth organizing happening all around our state. I spent the last few years organizing both on my campus at Virginia Tech, and bringing together students from across the region to form the Virginia Student Environmental Coalition (You can read more about me on the staff page).

I am absolutely overwhelmed at how much energy students are bringing to the People’s Climate March. Campuses across the state are mobilizing harder than I’ve ever seen, and it has me ready to work harder than ever. Already there are over 300 Virginia students planning to march this Sunday in New York City, joining more than 300 other campuses bringing thousands of students to march for our future.

The People’s Climate March is going to be the largest climate mobilization in history. With the problems we’re facing in Virginia due to dependence on fossil fuels–from severe flooding along our coast to severe asthma rates in Richmond to more severe storms just about everywhere–we need everyone there. Here are key updates on how you can: 1) Get to NYC; 2) March with the Virginia Student Environmental Coalition; and 3) Bring the momentum back to Virginia.

1) Getting there: Are you still looking for a ride? Here’s a rideboard for Virginia students to coordinate carpools to NYC. Please use it to form carpools from your area. Reminder: If you’re willing to use your car, please state how many seats you have! You can also check out the People’s Climate March ride board. Click here to see what’s available.

2) March with Virginia students: Virginia students will be marching as a block in the student delegation at the People’s Climate March. Check out the march line-up here. We will be meeting at Wagnar Cove in Central Park at 10:45 am. It’s a short walk from the 72nd Street subway station, and right in line with the student delegation. Make sure you and your delegation are there. We want to meet each other and march together to make Virginia student voices heard! For a map with the location of Sunday’s meet up point at Wagnar Cove, click here.

3) Join the call on September 24th: September 21st will be a big moment for our movement. We’re gearing up to bring that momentum back to Virginia — and keep up the pressure on our politicians and big corporate polluters like Dominion Virginia Power. To get rolling, we will be having a statewide Virginia Student Call on Wednesday, September 24th at 9pm. We will use this call to share major takeaways from the march, solidify our connections with new friends, and plan our next actions as a statewide youth network ready to combat climate change. Sign up here to join the Virginia Student Call.

The People’s Climate March is going to be big. Let’s come together and demand action on climate, both nationally and at home in Virginia.

Want to get your campus for involved in climate organizing? Email me at Drew@Chesapeakeclimate.org.

Appalachian Power Company Targets Two Solar Customers

On September 16th, Appalachian Power Company will ask the State Corporation Commission for permission to tax residential customers whose solar systems exceed 10kw in size. Some of you might be wondering how many APCo customers would be affected by the new tax. The answer? Two. That’s right, there are TWO people in APCo’s service territory who have solar systems larger than 10kw on their homes and the utility wants them to pay.

Prepare yourself as you try to follow their train of thought:

- Solar customers lower their utility bills by powering their homes with the sun

- However, these customers are still using the utility’s services when the sun isn’t shining and the solar panels aren’t generating electricity

- The burden to provide power to these customers on a part-time basis is onerous and forces them to pass costs to other customers

- The rest of APCo’s customers are unfairly subsidizing the “free-riders” who rely on the utility for power

- Thus, to be fair to everyone else, APCo must tax the “free-riders” to recover the costs

To put it another way: APCo is trying to make the argument that the only two customers with significant solar installations in their Virginia service territory are increasing the utility bills of APCo’s other 447,426 Virginia residential customers so much that the utility has no choice but to slap a tax on these two moochers in order to cover the cost.

Allow me to share a few facts. APCo’s rates have more than doubled since 2005 and it has nothing to do with solar energy. In fact, solar owners actually provide a benefit to utilities by providing excess grid power during times of high demand. And speaking of benefits, the CEO of APCo’s parent company, American Electric Power, earned more than $10 million in salary and benefits in 2013. And yet, APCo is spending an untold amount of money in staff time and legal fees to petition the SCC for the right to tax their two customers who have solar panels in excess of 10kw in size.

Head-scratching for sure.

Let’s take a dive into a few details of APCo’s request.

- The standby charges would apply to residential customers with solar installations between 10kw and 20kw in size (state law restricts residential customers from installing solar systems larger than 20kw)

- According to the filing, APCo will ask for distribution standby charges of $1.94/kw and transmission standby charges of $1.83/kw, totaling $3.77/kw

- Thus, homeowners with solar systems of 10kw would be taxed $37.70/mo in new standby charges, or $452.40/yr, with the potential for homeowners with the maximum-allowed 20kw solar systems of being taxed $75.40/mo or $904.80/yr

It goes without saying that taxing the sun is a silly idea. However, APCo is simply following the playbook first-written by Virginia’s utility behemoth Dominion Virginia Power. They’ve already successfully convinced the SCC to apply distribution and transmission standby charges to its customers who have similar-sized systems. Seeing this opportunity, APCo is seizing its moment to take advantage of its climate-conscious customers by imposing punishing taxes upon them.

Standby charges aren’t just a matter of economic fairness. They set a dangerous precedent that have the intention of suppressing the solar market. The state of Virginia is creating an environment that encourages the development of only the smallest of customer-owned solar systems. Homeowners who may wish to install large systems on their homes or property may think twice about crossing the 10kw threshold out of fear of being hit with taxes.

Standby charges send the wrong message during a time when the state needs to aggressively ramp up its solar energy mix. Solar prices are falling dramatically across the nation and as more citizens are educated about the benefits of solar, they are more encouraged than ever to make the switch from fossil-fuels to clean energy. Utilities everywhere are in a full-blown panic about the growth of customer-owned solar and are pulling out all the stops in order to stagnate its growth as much as possible.

The public comment deadline for APCo’s rate case is September 9th and the hearing is September 16th. Hopefully you will join CCAN in urging the SCC to not tax the sun and reject APCo’s proposed new standby charges.

Pricing Carbon, Paying Dividends Policy Update: August 2014

The Chesapeake Climate Action Network supports efforts to advance legislation to put a price on carbon and return all or most of the proceeds to American families. We are pleased to support HR 5271, the Healthy Climate and Family Security Act, “cap and dividend” legislation introduced by Congressman Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.) in the House of Representatives on July 30, 2014.

We will be producing and distributing this occasional newsletter to keep others informed about developments with this bill and with other efforts to put a price on carbon and other greenhouse gas emissions.

More information on the Van Hollen bill can be found at http://climateandprosperity.org.

In This Issue:

1. A Video Message from Rep. Chris Van Hollen

2. New York Times, July 30, 2014: The Carbon Dividend, by James K. Boyce

3. The Baltimore Sun, August 4, 2014: Cap and Dividend

4. The Washington Post, August 28, 2014: A climate for change: a solution conservatives could accept

5. The Santa Fe New Mexican: A smart strategy for fighting carbon pollution

6. Bloomberg Businessweek: Is This How to Sell Americans on Fighting Global Warming?

7. CCL Legislative Update: Rep. Van Hollen introduces cap-and-dividend bill

8. With Liberty and Dividends For All book review: Use Common Wealth to Reduce Inequality

#1: A Video Message from Rep. Chris Van Hollen (2 ½ minutes)

#2: New York Times, July 30, 2014: The Carbon Dividend, by James K. Boyce

“From the scorched earth of climate debates a bold idea is rising — one that just might succeed in breaking the nation’s current political impasse on reducing carbon emissions. That’s because it would bring tangible gains for American families here and now.”

Read the New York Times op-ed.

#3: The Baltimore Sun, August 4, 2014: Cap and Dividend

“In short, the concept makes a lot of sense — in terms of promoting conservation, reducing pollution and greenhouse gases and supporting renewable energy — with the added benefit of making such a transition a bit easier for anyone with a valid Social Security number. It is the ultimate consumer-friendly approach to a rational U.S. energy policy with the chief shortcoming being that it doesn’t serve the agenda of any deep-pocketed special interest group and so may have trouble finding broad support in Congress.”

Read the Baltimore Sun editorial.

#4: The Washington Post, August 28, 2014: A climate for change: a solution conservatives could accept

“This is not the first time that Rep. Chris Van Hollen (Md.), a House Democratic leader, has made the point that the best climate-change policy is not complicated. He introduced a similar plan in 2009. The underlying logic is older still: Since the beginning of the climate debate, mainstream economists, left and right, have argued that the best way to cut greenhouse gases is to use simple market economics, putting a price on emissions that reflects the environmental damage they cause.”

Read the Washington Post editorial.

#5: The Santa Fe New Mexican: A smart strategy for fighting carbon pollution

“I’m a University of New Mexico student who works full time to make ends meet. I support this bill because I think we need to make the price of carbon-polluting energy sources reflect their true costs — in terms of the environment and our children’s futures, so we shift away from these sources to cleaner energy supplies. Secondly, I think regular people like me and my working-class family need to have help making the transition.”

Read the op-ed.

#6: Bloomberg Businessweek: Is This How to Sell Americans on Fighting Global Warming?

“The bill would require companies to have permits to produce or import carbon-containing fuels such as oil, coal, and natural gas. The permits, instead of being allocated politically, would be auctioned off by the government, so they would get into the hands of the emitters who need them the most. A similar auction system drastically reduced emissions of sulfur dioxide—which causes acid rain—quicker and cheaper than experts expected.”

Read the full Bloomberg story.

#7: CCL Legislative Update: Rep. Van Hollen introduces cap-and-dividend bill

“The introduction of this legislation shows that we have moved legislators — especially Democrats — a long way toward revenue-neutrality in carbon pricing, as well the concept of returning revenue to households as dividends. This is an important step forward as we seek bi-partisan legislation, and we’re thrilled with Van Hollen’s bill from that standpoint.”

Read the CCL update.

#8: With Liberty and Dividends For All book review: Use Common Wealth to Reduce Inequality

“One beauty of his proposal is that the income everyone receives would come without political or psychological stigma. The dividends couldn’t be criticized as reckless government spending or money taken through taxation. Nor could they be called a handout to the ‘undeserving poor.’ Dividends from common wealth would be a universal birthright, and that is a big part of their appeal. Chase down a copy of With Liberty and Dividends for All. It will challenge many of your assumptions about what we can accomplish within a market economy and within the framework of the commons. The reverberations from this short, readable and profoundly original book will be heard for years to come.”

Read the full review.

CCAN encourages readers of Pricing Carbon, Paying Dividends to distribute it to others who might be interested. We welcome input on the contents of this publication and ideas for what could be included.

Send to Ted Glick at ted@chesapeakeclimate.org.

A 40% Clean Electricity Standard Would Put Maryland on the Cutting Edge

CCAN and our partners will be fighting over the next year to double Maryland’s commitment to clean electricity. Burning dirty coal, oil and gas for electricity remains the single largest source of statewide greenhouse gas emissions, and so it’s essential that Maryland transitions as quickly as possible to clean, non-polluting sources. Our state’s current requirement is 20% clean electricity by 2022, and we want to double that to 40% by 2025. This 40% clean electricity standard would put Maryland on the cutting edge of renewable energy policy, and it would go a long way toward increasing national momentum behind a clean energy economy.

A 40% clean electricity standard for Maryland would incentivize enough clean energy capacity to offset about 10 coal-fired power plants, and it would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by over 9.7 million metric tons per year. That’s the carbon equivalent of taking 2 million passenger vehicles off the road every year, which will deliver improved public health outcomes, cleaner air and cleaner water for Maryland and our region.

This 40% clean electricity standard for Maryland is ambitious, and in fact it is eminently achievable. The operators of our regional electricity grid recently released a study that examined the grid impacts of doubling current clean electricity levels in states in our region over the next decade. They included the cost of coping with the intermittency of wind and solar as well as the costs of major transmission upgrades that would likely be needed. The very good news is that the study concluded that grid “will not have any significant issues” if each state doubled its own clean electricity standards. In fact, the study found that we would reap significant benefits by accelerating our clean electricity generation, including maintenance of reliability, reduced emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants, and lower energy costs.

So, Maryland can and should get to 40% clean electricity as soon as we can, and that’s what we’ll be pushing for in the coming months. Stay tuned for updates and ways to get involved, and check out more on the campaign here: http://chesapeakeclimate.org/maryland/40-percent-rps/

Letter from the Director: Why I'm an optimist

Dear CCAN supporters,

They say you have to be an optimist to be an activist. So I guess I’m an optimist. Despite the admittedly dark days and setbacks that come with fulltime campaigning on global warming, I know that a totally clean-energy world is within our grasp in our lifetimes. I believe this with every fiber in my body. So yeah, I’m an optimist. And you should be too! Read through to the end of my column to see why.

But first, let’s not sugarcoat things. After a long career in journalism, I founded CCAN in 2002 because I had come to realize that nothing else – nothing – was as important as fighting global warming. We could cure cancer tomorrow but we won’t have good health if malaria spreads and heat waves and droughts leave us malnourished. We could end all wars forever, and we won’t have peace if warming-induced Frankenstorms like Sandy and Katrina batter our coastal cities. A wise scientist once said, “Climate is destiny. Change your climate and you change everything.”

Each time I read or hear of some new natural-world weirdness I look for the fingerprints of climate change and they are almost always there. The massive algae bloom in Lake Erie that recently contaminated the drinking water of more than 400,000 people in the Toledo, Ohio region? It wasn’t the heat this time. It was, according to a state official, the incredible increase in “extreme rain events” that have recently plagued Ohio. Scientists confirm that measurable and growing extreme precipitation events are being triggered by global warming in much of the country. A warmer atmosphere holds more moisture. But what goes up eventually must come down. And we’re learning that it tends to come down in bursts. Those bursting rain events this summer have swept record amounts of livestock waste and agricultural fertilizer into Lake Erie during concentrated periods of time that have in turn triggered unprecedented algae blooms that knocked out the drinking water to nearly half a million Ohioans.

Of course, similar disruptive events related to climate change are happening worldwide. A draft report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, just released this week, states that climate change is now “severe” and “pervasive” and some characteristics of it are “irreversible.” The report is the scientific community’s starkest and most strongly worded warning yet of the dangers that lie ahead unless we act.

And so we must act. CCAN has never been busier in the fight to reduce carbon pollution in our region. We continue to battle the ridiculous and destructive proposal to build a fracked gas export facility at Cove Point in Maryland. We’re fighting drilling and new gas pipelines across the region. And we push just as hard for clean-energy solutions like offshore wind in Virginia and a mandatory doubling of clean electricity in Maryland.

But here’s the main reason — in addition to the historic People’s Climate March — that you should be an optimist despite the UN report and water contamination in Ohio and all the rest. On July 30th, prominent U.S. Congressman Chris Van Hollen (D-Md) introduced The Healthy Climate and Family Security Act of 2014. I’ve never seen a more just and affective piece of legislation aimed at “de-carbonizing” the American economy. The Van Hollen bill puts a strong and transparent cap on carbon emissions, forces polluters to pay for any harm they do to the atmosphere, and rebates the collected money on a quarterly basis to every single American with a social security number. This idea could WORK. The Washington Post and Baltimore Sun agree. Now it’s our job to build a climate movement that persuades Congress and our President to embrace this policy before it’s too late.

Learn more about the Van Hollen bill at www.climateandprosperity.org. And stay tuned for exciting action alerts from CCAN throughout the autumn.

Your optimist,

Mike Tidwell

Natural Gas in Virginia: Dominion’s proposed pipeline and how we can stand together to fight back

Update as of November 13th, 2014:On October 31st, Dominion Resources submitted a pre-filing request to FERC, the Federal Energy Regulatory Committee, which asks them to begin the environmental review of the pipeline. Landowners, community members, and activists around the state are continuing to mobilize and fight Dominion’s FERC requests at every step of the process. CCAN has partnered with local groups on the ground to launch a petition to Governor McAuliffe asking him to renounce his support of the pipeline. Our goal is 10,000 signatures–help us reach our goal and stop the Atlantic Coast Pipeline by signing here!

As of November 12th, Dominion gave final notice and threat to sue the 189 landowners along the path of pipeline who have not issued permission for Dominion to survey their land. If you have received a letter from Dominion and need more information, please contact: info@augustacountyalliance.org.

As Virginians, we’ve been fortunate enough so far to be free of fracking—the dangerous process of hydraulic fracturing for natural gas.

But just because we aren’t on top of the Marcellus Shale or Utica Shale basins, doesn’t mean we’re not connected with our neighbors battling fracking wells in their backyards, or that the dangers of our nation’s natural gas boom aren’t already threatening Virginia.

Dominion Resources recently partnered with Duke Energy, Piedmont Natural Gas, and AGL proposed a $5 billion, 550-mile pipeline that would cross through Virginia to connect natural gas production in West Virginia to consumption in North Carolina.

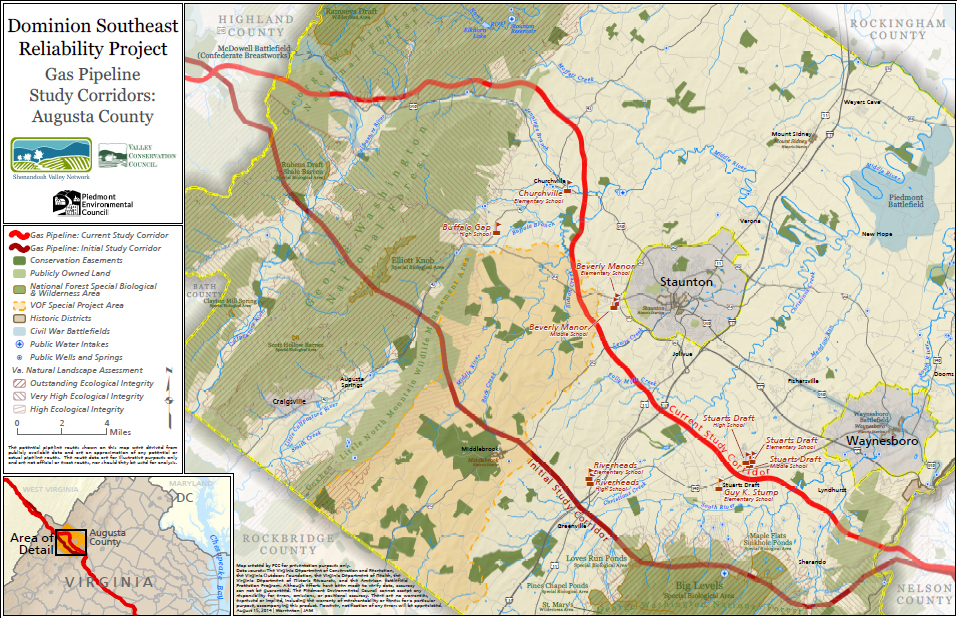

Starting in West Virginia, Dominion’s Atlantic-Coast Pipeline (previously known as the Reliability Pipeline) would enter through Highland County, heading into Nelson County and across the Shenandoah Valley on its way to North Carolina. The pipeline would also have an extension connecting to Hampton Roads. The proposed route would go through the George Washington National Forest and the backyards of Virginian families.

Leaks, explosions, and other accidents are not unlikely for a project of this scale, and hundreds of Nelson County residents raised their safety and environmental concerns last week at Dominion’s first public meeting in Nelson County.

Here’s a close up of the contested route, provided by groups helping to organize local residents to fight back:

I think a more reliable project wouldn’t include the risk of gas leaks and explosions. A smarter investment would be putting that $2 billion into energy efficiency, wind, and solar energy for our region.

Instead, it’s very clear that Dominion is moving too far, too fast towards natural gas, yet another dangerous fossil fuel — and one comprised mostly of methane, a powerful heat-trapping gas known to leak at high levels during the fracking process.

In fact, Dominion Virginia Power’s Integrated Resource Plan proposes 6-7 new fossil fuel plants in Virginia over the next 15 years, and Dominion Resources (DVP’s parent company) is fighting hard for a $3.8 billion liquefied natural gas export facility in Cove Point, Maryland. It’s clear that this pipeline is one major piece of Dominion’s region-wide push to keep us locked into climate-harming fracked gas for decades to come.

Unless we stop it.

Groups of concerned citizens across the Commonwealth are banding together to resist this pipeline—and to resist all dangerous, new natural gas pipelines and infrastructure that are a threat to our state.

Please check out the following organizations that are coordinating regional resistance to the pipeline and supporting homeowners along the proposed routes. Join their mailing lists for immediate updates on the pipeline routes as they continue to unfold:

Friends of Nelson County

- Serves Nelson County,VA

- An association of Nelson County residents, landowners and other concerned citizens who are opposed to the construction of the Dominion Southeast Reliability Pipeline crossing through Nelson County

- http://friendsofnelson.com/

- Like them on facebook: https://www.facebook.com/freenelson2 and https://www.facebook.com/No.Nelson.Pipeline

Shenandoah Valley Network

- Serves Augusta County, Frederick County, Page County, Rockingham County, Shenandoah County, Warren County

- Working to protect and sustain the rural landscapes, communities, and ecosystems of the Shenandoah Valley by working with strong local citizens’ groups, promoting smart local land use, and effective land protection strategies

- http://www.svnva.org/

Augusta County Alliance

- Serves Augusta County

- Dedicated to preserving the rural landscape, economy, clean air and water of Augusta county

- Currently sending “know your rights” letters to landowners along the pipeline route

- http://augustacountyalliance.org/

- Like them on facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AugustaCountyAlliance

Highlanders for Responsible Development

- Highland County, VA

- Highlanders for Responsible Development is a citizens’ group that promotes stewardship of Highland County’s unspoiled landscape, natural resources and exceptional quality of life. We support policies and activities that are based upon informed community discourse, democratic decision making, prudent land use and sustainable economic development.

- http://www.protecthighland.org

Visit us back here for more updates as they unfold. CCAN will be keeping all eyes on the pipeline route and the proposal process to make sure we inform supporters with the first opportunity for public comments and other actions we can take statewide to stop the pipeline.

For updates on the pipeline project: http://www.nelsoncounty-va.gov/pipeline-information-and-updates/

Maryland Study Shows that Protecting Our Health Requires Keeping Fracking Out

Children with unexplained nose bleeds. Babies born with birth defects. Workers sickened by exposure to toxic, tiny silica particles. These are just some of the health impacts linked to the fracking already happening in states from Texas to Colorado to neighboring Pennsylvania.

On Monday, the O’Malley administration released a study, prepared by researchers at the University of Maryland, aimed at assessing the potential public health impacts of allowing fracking in Maryland. The findings are alarming and, health experts are saying, only scratch the surface of the harm our communities could face if this volatile, toxic form of drilling were allowed in Maryland.

I’ve summarized below three main things every Marylander should know about this report.

The O’Malley administration is taking public comments on the report through October 3rd, so click here to take action today.

#1 Fracking is likely to cause serious harm to the health of Maryland residents and workers.

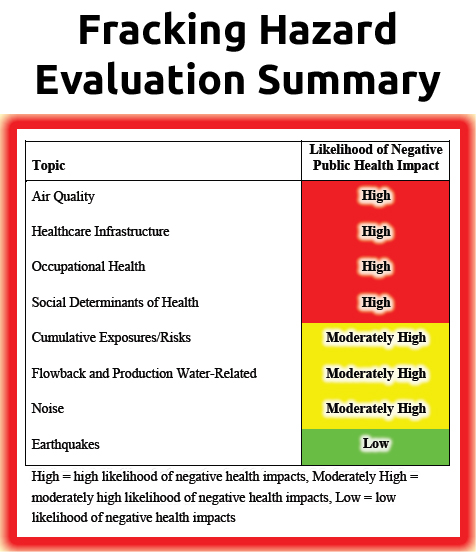

The table on the left summarizes the overall “hazard” rating that the UMD researchers assigned to each impact category they considered. Air pollution is one of the major health concerns, along with workers’ safety, the burden on local health care infrastructure, and negative impacts on the mental and social health of communities, for instance through increases in sexually transmitted diseases, crime, traffic injuries, and substance abuse.

Dr. Gina Angiola, a retired obstetrician and board member of Chesapeake Physicians for Social Responsibility, summarized in response, “This report confirms that unconventional natural gas development has the potential to cause both short-term and long-term health impacts, some of which may be irreversible.”

Air pollution is of particular concern because fracking operations emit a variety of toxins linked to cancer, birth defects, and respiratory illnesses. The study underlines that peer-reviewed research is beginning to emerge linking air pollution associated with fracking to “increased risk of subchronic health effects, adverse birth outcomes including congenital heart defects and neural tube defects, as well as higher prevalence of symptoms such as throat & nasal irritation, sinus problems, eye burning, severe headaches, persistent cough, skin rashes, and frequent nose bleeds” (p. xx) among people living within 1,500 feet of gas drilling facilities.

Or, as the Think Progress news headline on the Maryland study summed up, “Fracking in Maryland Would Threaten the Health of Anyone Who Breathes Nearby.”

#2 The Maryland health study only scratches the surface of the risks we could face, leaving more questions than answers.

To add important context, the health study was released as part of a fracking review process initiated by Governor O’Malley in 2011. Through an executive order, the governor placed a defacto moratorium on fracking in Maryland and ordered a series of studies aimed at determining whether or not fracking would pose unacceptable risks to the state’s public health, safety, environment and natural resources. The 2011 executive order originally set a deadline of August 1, 2014 to complete this review; after much delay, a final report is now expected from state agencies this fall. From the start, the process has been compromised by insufficient funding, rushed timelines, and incomplete or flawed studies.

The health study falls clearly into the rushed and incomplete category. Rebecca Ruggles, director of the Maryland Environmental Health Network (MdEHN), said following the report’s release, “Marylanders should not become the next guinea pigs for testing the gas industry’s impact on people. This report should be viewed as Maryland’s first, not last, inquiry into health impacts. The work is not complete.”

For one, the study’s scope was highly limited by insufficient funding and a rushed timeline. For example:

- The study looked only at potential health impacts in Western Maryland — even though gas basins lie underneath 19 Maryland counties statewide, and the impacts of gas compressor stations and other fracking-related infrastructure could extend statewide.

- The study didn’t look at the costs of lost work and school days due to illness, or of the increased demand for emergency and other healthcare services.

- The study didn’t adequately address how our farms, food and livestock would be impacted by potential soil and water contamination.

- The study didn’t consider the health impacts of worsening climate change – the #1 long-term health threat we all face – due to emissions of methane, a potent heat-trapping gas.

Second, and perhaps even more importantly, health experts, including the study’s authors, caution that medical knowledge on the health outcomes related to fracking is still “extremely limited” (see the summary of limitations on p. 100 of the report).

Comprehensive epidemiological studies of fracking’s health impacts are few and far between, or only in the beginning stages in places where drilling already occurs. Aaron Bernstein, associate director of the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard University warned in February that scientists “really haven’t the foggiest idea” how fracking impacts public health, primarily because of inadequate research and monitoring to date.

While the University of Maryland study includes 52 recommendations for minimizing the potential health risks of fracking, these recommendations fail to address all of the safety concerns raised by the report. Furthermore, there is little to no scientific evidence proving that recommended steps — such as setting drilling wells back from homes by only 2,000 feet — would be sufficient to protect our health.

Underscoring this point, Dr. Jerome Paulson, MD, director of the Mid-Atlantic Center for Children’s Health & the Environment and a professor of pediatrics at George Washington University wrote in a June letter to Pennsylvania’s Secretary of Environmental Protection, “There is no information in the medical or public health literature to indicate that [unconventional gas extraction] can be implemented with a minimum of risk to human health.”

#3 To protect Marylanders’ health, Governor O’Malley must keep our state’s fracking moratorium in place.

“First, do no harm.” It’s a basic tenet of medical practice, and it’s a tenet that Governor O’Malley and his successor in office must apply when it comes to fracking and the health of Marylanders.

“First, do no harm.” It’s a basic tenet of medical practice, and it’s a tenet that Governor O’Malley and his successor in office must apply when it comes to fracking and the health of Marylanders.

Given the alarming emerging evidence on the risks fracking poses to our health, and the many unanswered questions, Governor O’Malley must keep Maryland’s fracking moratorium in place. By doing so, the governor will be keeping his promise to ensure a science-based decision on fracking. As long as we don’t have the full answers we need and deserve on the health dangers, no fracking should happen in Maryland — period. At the bottom of it all, our health is worth far more than the short-term profits of the oil and gas industry.

Click here to submit a public comment on the health study and urge Governor O’Malley to keep our fracking moratorium in place.

Eastern Shore Wind Farm vs. Naval Air Station: Take 2

VIRGINIA SEEKS PUBLIC COMMENT ON EPA’S CARBON REDUCTION PLAN

Virginia’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) has just wrapped up a series of listening sessions last week, eliciting public feedback on the EPA’s new draft rules for carbon reductions for existing power plants. These rules, known as the Clean Power Plan, or “111(d)” as policy wonks call them, are the signature components of the President’s Climate Action Plan and are designed to make America the leader in the fight against climate change by reducing the nation’s CO2 by 30% by 2030. (In case you’re wondering, 111(d) is the code section of the Clean Air Act which gives the EPA the authority to regulate CO2). Virginia’s specific carbon reduction target is 38% below 2012 levels by 2030.

The DEQ listening session took place in Henrico on Thursday night. Four speakers representing various co-operatives and the VA Chamber of Commerce spoke in opposition of the draft rules, a modest effort and fine showing if it were not dwarfed by the 24 citizens and environmental representatives speaking passionately about the need to support the rules and fight against climate change.

As expected, the dirty polluters spouted the familiar tired arguments: efforts designed to cut carbon pollution would increase rates, reduce jobs, and stymie economic productivity. These arguments fly in the face of numerous studies suggesting that smart investments in renewable energy and energy efficiency can actually provide a cool billion dollars in energy savings for Virginia customers, while adding 21st century jobs and providing a spark to the clean energy economy.

Further, reducing harmful carbon pollution from our environment has the added benefit of improving the public health of the commonwealth’s 8.2 million residents. While Virginia has much to be proud of, its capital city of Richmond winning the Asthma and Allergy Foundation’s “Asthma Capital” award not once but TWICE should be enough to give rule-makers pause.

If that weren’t enough, coal’s pollution has a well-documented disproportionate effect on many minority and other low-income communities. In fact, the NAACP recently released a stunning report highlighting that 68% of blacks in America live within 30 miles of a coal-fired power plant. Our friends at Virginia New Majority provided much-needed and oft-overlooked testimony to this disparity during the Henrico hearing on Thursday.

And oh by the way, rising seas, devastating storms, punishing droughts, and other climate disruptions will be mitigated by reducing carbon pollution in the environment. Added all up and the benefits v. harms of the Clean Power Plan are as lopsided as the 24-4 representation DEQ witnessed at its listening session in Henrico.

DETAILS ON THE CLEAN POWER PLAN

EPA outlined four “building blocks” for states to use in order to meet the carbon reduction goals. These four options are available for states to use and experiment with, allowing each state maximum flexibility in determining which mechanism, and to what extent, the state should use to achieve its goal. The building blocks are:

1) Heat rate improvements at coal-fired power plants,

2) Shifting dispatch from coal to natural gas,

3) Increasing renewable and nuclear generation, and

4) Increasing demand-side energy efficiency

Building block number two for the state’s consideration, swapping coal for natural gas, is akin to a Vicodin addict swapping the pills for a steady diet of Jack Daniels. Gone is the Vicodin addiction, as well as the pain temporarily, but the long-term effects of severe alcoholism can be equally as damaging, if not more-so, than the initial problem.

Our nation’s longtime dependence on coal has been a danger to climate stability. But a fast switch to natural gas as the solution to the coal dependency is not the answer. Methane leakage from the production, transport, and usage of natural gas accounts for nearly 10% of U.S. greenhouse gas pollution, ranking 2nd behind CO2. Over a 100 year period, methane emissions are more than 20 times more potent of a climate change pollutant than CO2, which makes a switch from coal to gas seem more like a dodge than a direct attempt to solve the climate problem.

Virginia has incredible untapped potential for efficiency, solar, and particularly offshore wind. These resources need to be fully tapped before other options are considered.

TIMELINE FOR IMPLEMENTATION

The draft EPA rules were first announced on June 2, 2014 and made official on June 18, 2014. Since then, DEQ has organized listening sessions to provide feedback on the rules. EPA asks that all entities (citizens, businesses, government agencies like DEQ, etc.) to submit comments back to EPA by October 16, 2014.

Thereafter, EPA will develop its final and binding carbon reduction rules to be released in June of 2015. Virginia will have one year, until June 30, 2016, to provide EPA with a detailed State Implementation Plan, outlining how the commonwealth will achieve its carbon reduction goals.

Virginia has the option of achieving the goals on its own, or by joining a multi-state collaboration like the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). If Virginia decides to join RGGI, a collaborative with proven success and one in which CCAN steadfastly urges the state to join, it will have until June 30, 2018 to do so and outline its intention to achieve the goals under the final rules proposed by EPA.

All states have until 2030 to achieve its state-specific carbon reduction goals – until 2032 to ensure the carbon reduction goals are met under three years averages for 2030, 2031, and 2032. CCAN will be there every step of the way to ensure Virginia makes the right decisions for our climate.